Histology is the study of tissue, and osteohistology is the study of bone tissue. Medical doctors and veterinarians study soft tissue and bone samples to look for disease, abnormalities, etc. Paleontologists study bone tissue to look for evidence of the life history of an extinct animal. Only in the past few decades have paleontologists come to understand the wealth of information that can be gained from studying bone tissue. The internal microstructure of bone tells us about how an organism grew and how intrinsic and extrinsic factors affected how an organism grew. Specifically, evolutionary relationships (phylogeny), age of the organism (ontogeny), how the animal used the bone (biomechanics), and environment directly influence bone growth. How an animals grows then tells us specifically about the life history of that animal: rate of juvenile development, age of sexual maturity, growth rate, etc.. To study bone tissue on a level that gives us useful information, one looks at just a thin sliver of the bone under a microscope. This requires cutting a chunk out of the middle of the bone, gluing it to a slide, and grinding it thin enough so light shines through the bone. Of course we photograph, measure, and make replicas (molds and casts) of the bone before cutting, but this process obviously permanently alters a bone.

|

| Schemtic drawing of internal bone structure showing possible features that may be present. |

|

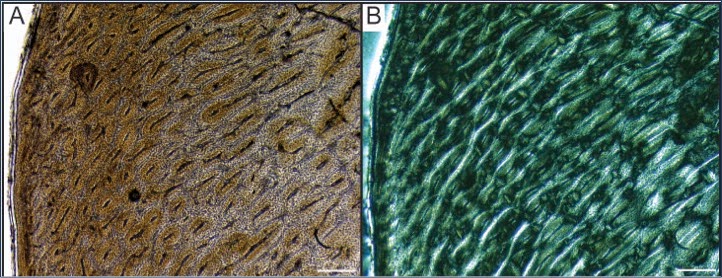

| Cross section through a Gentoo Penguin femur under plain light (A) and polarized light (B). Under polarized light (B), collagen fibers become apparent (the light and dark regions show changes in collagen fiber orientation). Gentoo penguins were one of three modern penguins species used to help interpret fossil bird bone in a study I recently published. |

Histology is often the focus of studies pursuing a better understanding of ontogeny, paleoecology, and behavior. Even descriptions of new species often include bone histology. Knowing that an animal is an adult (and has completed development and growth) is important when describing a new species. Studying bone microstructure is the only way to determine if an animal had reached skeletal maturity by the time of death - in other words, whether the animal was an adult at the time of death. Because of all we can learn from fossils by cutting them open, histology is a rapidly growing field in paleontology. We are at a point where very few (at least in my experience) paleontology curators and collection managers (those who permit access to fossil for research purposes) don't permit researchers to section at least some bone for histology research.

Studying the internal microstructure of bone is a research trend that isn't going away any time soon - and this is a good thing. There is too much valuable information yet to be uncovered that can come from studying bone growth. As one of my primary research focuses is on osteohistology, I sometimes find myself getting defensive when explaining my research to a lay audience. I feel that I need to justify why destructive analysis (or permanently altering bone, which sounds at least a bit more innocuous) is important. Luckily I have generally found that explaining the range and depth of information that can be gained from histology is very effective in relaying the significance of this research. Perhaps this research method doesn't seem so destructive when you consider how much information can only be gained by cutting open bone. Knowing that we make replicas of everything we sample also helps.

So while paleontologists work hard to preserve fossils, the goal of preserving them is to use these fossils for education and research. Sometimes the quest for knowledge requires seemingly unconventional research methods. Histology has opened our minds to how extinct animals grew from hatching/birth to adulthood, how these animals responded to their physical environment, what their metabolism was like. It has also provided valuable information about the growth and development of modern animals! Bone microstructure has provided information that we could not imagine knowing just a few decades ago. It may seem paradoxical to alter bone to advance the science of paleontology, but in the case of bone histology, I feel it is clear that the ends justify the means.